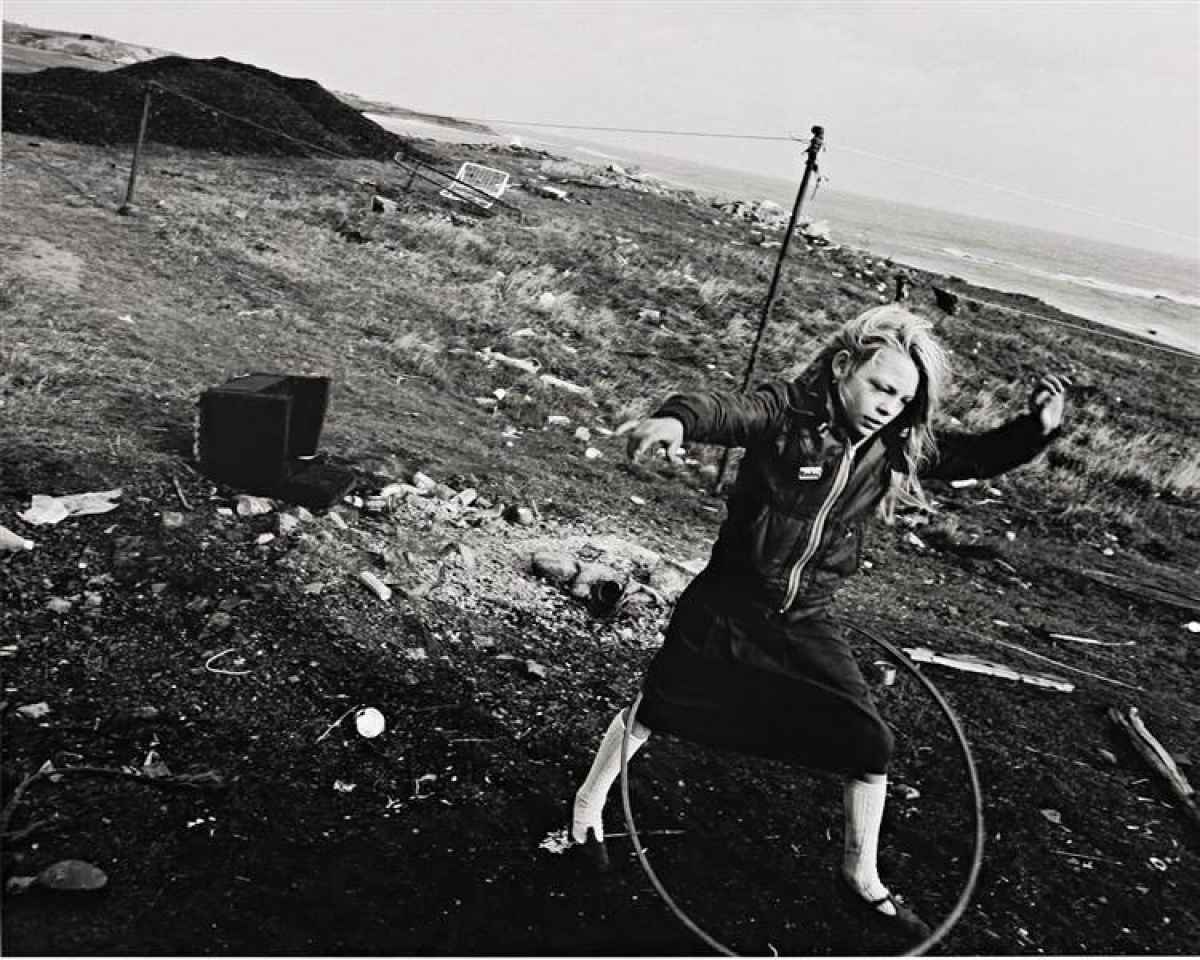

Cookie in the snow, Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, 1985, by Chris Killip.

on winter’s edge

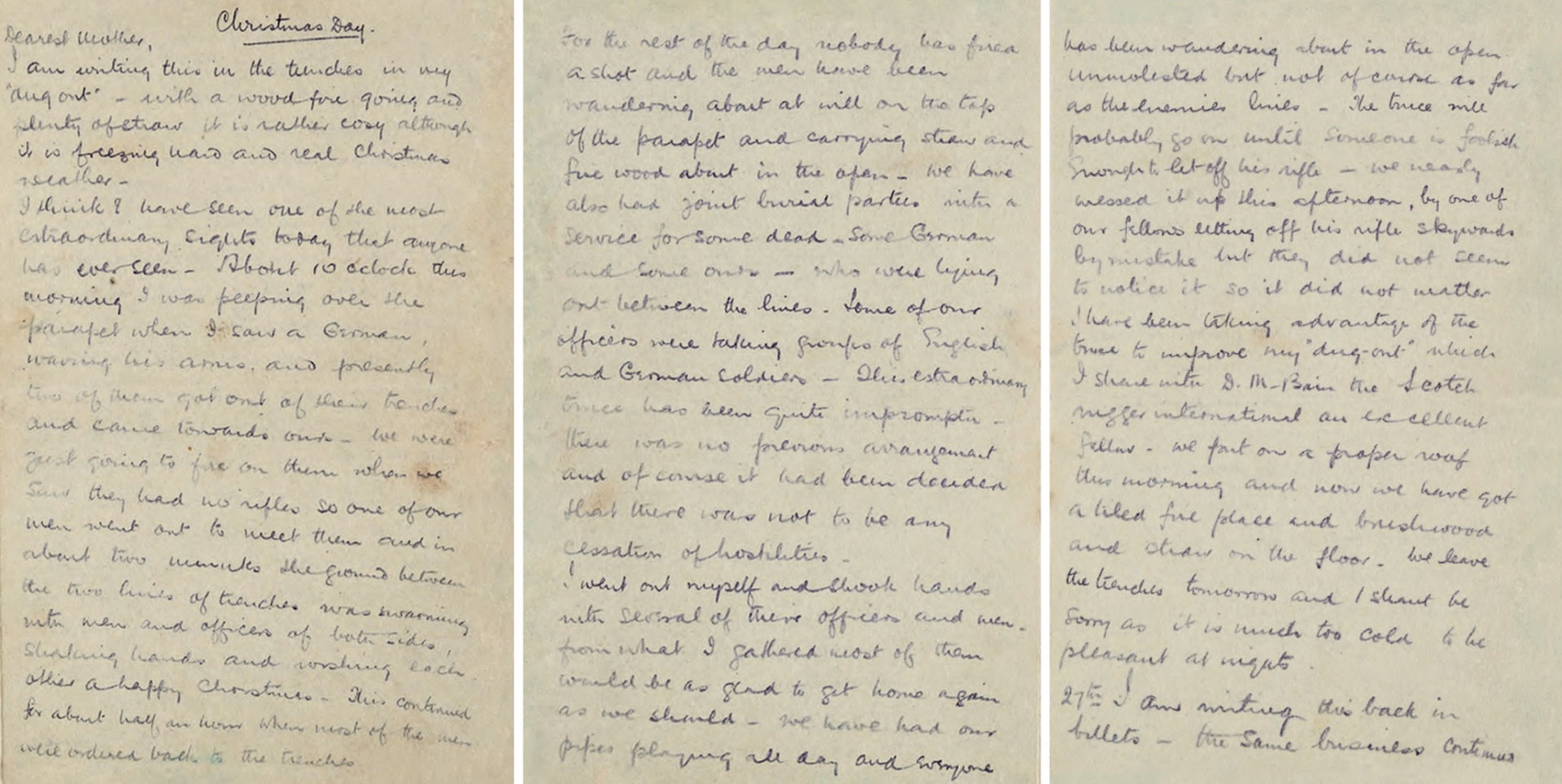

christmas truce letter from the trenches

From the Guardian:

From the Guardian:

It was penned 100 years ago in the freezing trenches of the western front; a letter from a British army officer to his mother describing in vivid detail the extraordinary Christmas truce as soldiers from both sides laid down their weapons.

Second Lt Alfred Dougan Chater, of the 2nd Gordon Highlanders, writes of the moment when the men met in no-man’s land, exchanging souvenirs and cigars as impromptu truces were held along parts of the front between Christmas and New Year, with joint burial parties for the dead.

The letter has been reproduced by the Royal Mail, with permission from the Chater family, to mark the anniversary of the historic truce and the role played by the postal service during the first world war.

Remarkably, Dougan mentions nothing about Sainsbury’s or having a Sainsbury’s branded experience of the truce that day in 1914.

Dated Christmas Day and signed “Dougan”, the letter reads: “Dearest Mother, I am writing this in the trenches in my ‘dug out’ – with a wood fire going and plenty of straw it is rather cosy, although it is freezing hard and real Christmas weather.

“I think I have seen today one of the most extraordinary sights that anyone has ever seen. About 10 o’clock this morning I was peeping over the parapet when I saw a German, waving his arms, and presently two of them got out of their trench and came towards ours.

“We were just going to fire on them when we saw they had no rifles, so one of our men went to meet them and in about two minutes the ground between the two lines of trenches was swarming with men and officers of both sides, shaking hands and wishing each other a happy Christmas.

“This continued for about half an hour when most of the men were ordered back to the trenches. For the rest of the day nobody has fired a shot and the men have been wandering about at will on the top of the parapet and carrying straw and firewood about in the open – we have also had joint burial parties with a service for some dead, some German and some ours, who were lying out between the lines.”

He writes of shaking hands himself with several of the German officers and subsequently describes another “parley with the Germans in the middle” where cigarettes and autographs were exchanged and “some more people took photos”.

Watch the Sainsbury’s 2014 Christmas commercial ‘Christmas is for sharing’ and read my post about it here, or listen to what Russell Brand thinks of it here.

For some real, unbranded history, visit the First World War galleries on the Imperial War Museum’s website.

russell brand on sainsbury’s christmas ad

Yes, in their 2014 Christmas commercial that re-imagines the 1914 Christmas truce, Sainsbury’s has reduced World War I to nothing more than a branding opportunity to exploit. Which means they’re also exploiting the people who died after this historical event ended and killing resumed. It’s a piece of history they’re trying to rebrand as a Sainsbury’s feel-good moment, and it’s a cheap manipulation, an attempt to transfer some of the mythology of that poignant historical moment to the Sainsbury’s brand. As Russell says, ‘football, love, chocolate — is nothing sacred?’ You can read my original post on Sainsbury’s 2014 Christmas commercial here.

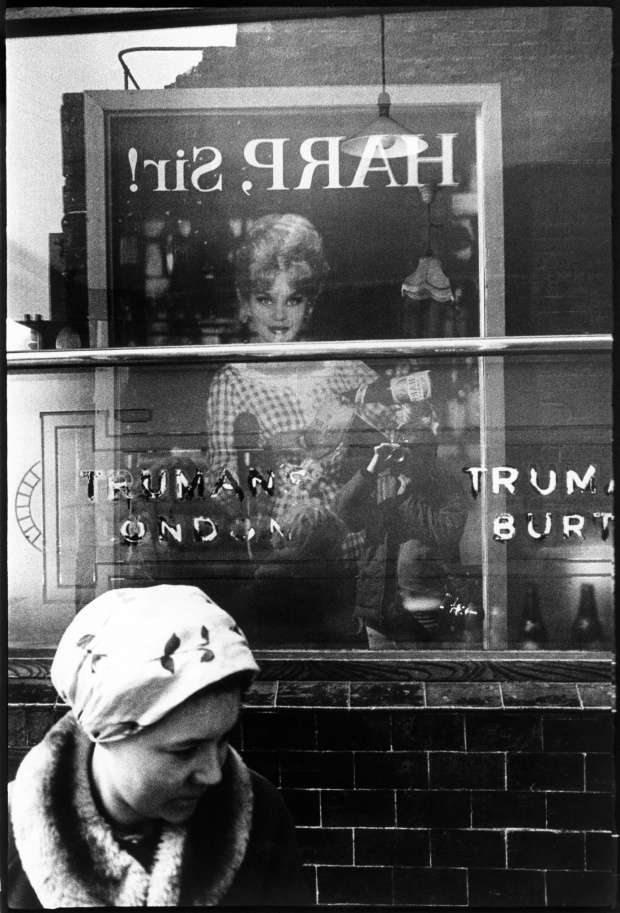

david bailey: east end woman, 1960s london

From the Guardian’s series ‘my best shot,’ David Bailey tells the story behind this photo, taken around 1961:

The shot’s a statement on the social climate at the time – and at any time really. I was living in the East End in the 60s, which was probably more of a nightmare than living there through the war.

[ … ]

I sort of remember the day. But there were lots of days like it. I’d spend maybe eight hours taking pictures round the East End. I wasn’t just mindlessly clicking away, though. I’d think about things: you have to. I’m not one of those photographers who doesn’t know what he’s doing, so takes hundreds of pictures in the hope there’s one good one. I do one click then move on. By the look of the picture, it was quite sunny – the reflection wouldn’t have been as strong otherwise. I prefer London in the rain, though. I just find it so beautiful.

I started shooting in the East End because it was where I was from. I lived there all through the blitz. When I was about three and a half, the flat next door was flattened, so we had to move from Leytonstone to East Ham. I was six and a half when the war ended and quite used to bombsites by then. I’ve never let myself be limited by my background, though.

chris killip: helen and her hoola-hoop

Chris Killip: Helen and her hoola-hoop, Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, Northumberland. This and many other exquisite photos are included in the book Chris Killip: In Flagrante.

sainsbury’s christmas truce, 1914

In the last of the series for 1914, veterans of the First World War recall the few hours of impromptu ceasefire on 25th December 1914, when German and British troops mingled and played football in No Man’s Land on the Western Front. Drawing on the recollections of soldiers in the oral history collection of the Imperial War Museum and the BBC archive. Narrated by Dan Snow.

There are now no living veterans of WW1, but it is still possible to go back to the First World War through the memories of those who actually took part. In a unique partnership between the Imperial War Museums and the BBC, two sound archive collections featuring survivors of the war are brought together for the first time. The Imperial War Museums’ holdings include a major oral history resource of remarkable recordings made in the 1980s and early 1990s with the remaining survivors of the conflict. The interviews were done not for immediate use or broadcast, but because it was felt that this diminishing resource that could never be replenished, would be of unique value in the future. Among the BBC’s extensive collection of archive featuring first hand recollections of the conflict a century ago, are the interviews recorded for the 1964 TV series ‘The Great War’, which vividly bring to life the human experience of those fighting and living through the war.

henley regatta

remember, remember the 5th of november

vladimir sokolaev: life in the soviet union

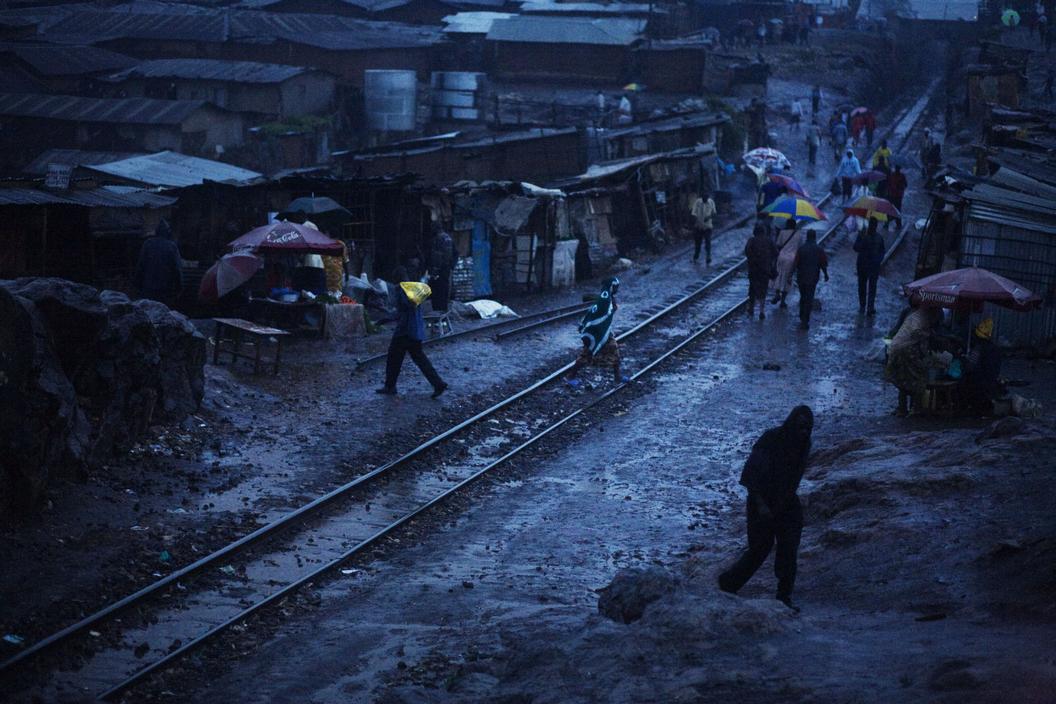

the places we live: jonas bendiksen

Mumbai, India, 2006. A photographic reconstruction of the Shilpiri household, from Magnum photographer Jonas Bendiksen’s book The Places We Live. In the book’s introduction, Philip Gourevitch writes,

Mumbai, India, 2006. A photographic reconstruction of the Shilpiri household, from Magnum photographer Jonas Bendiksen’s book The Places We Live. In the book’s introduction, Philip Gourevitch writes,

To see these lives, you must enter their space, and Bendiksen leads you in. . . . This is how we live: a billion of us in a billion different ways. These photographs have surmounted the most debilitating aspect of how we perceive poverty, the vocabulary of grinding sameness by which lives of little means are conventionally described.

. . . There is no denying that Bendiksen’s photographs are not simply documents or evidence of our times, but rather their power resides not only in the information they communicate but in the manner in which they communicate it—formally, aesthetically, dramatically.

Bendiksen explains the story behind the book’s photos:

Between 2005 and 2007, I spent many months in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya; Mumbai, India; Jakarta, Indonesia; and Caracas, Venezuela, trying to glean an understanding of what daily life is like for the people who live there. The neighbourhoods pictured in this book are some of the densest places on earth. Cramped homes, often just a single room, provide little privacy for their occupants. Encapsulated in these spaces are complete domestic universes, everything a family owns. Here, the improvised wallpapers, self-built furniture, knickknacks, and memorabilia form clues to what it means to be an urban citizen in the twenty-first century. I photographed each of the four walls in every home I visited. The residents of each home appear in one of these images.

‘Tell me about life here,’ I said. I hoped that they would talk about whatever they felt like—their homes, families, dreams, hopes, jobs, frustrations, or fears. This book is a collection of their voices and reflections on living in the world’s fastest-growing human habitat—the slums. These are the places we live.

Jakarta, Indonesia, 2007. Street vendor in Tanah Abang, a slum area that hugs several commuter railway lines.

Jakarta, Indonesia, 2007. Street vendor in Tanah Abang, a slum area that hugs several commuter railway lines.

Mumbai, India, 2006. A little girl playing in Laxmi Chawl, a neighbourhood of Dharavi. The little lightbulbs are put out for an upcoming neighborhood wedding.

Caracas, Venezuela, 2007. New squatter settlements on a hillside in north Caracas.

Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. Scenes from Kibera, Africa’s largest slum, where almost one million people live on less than a square mile.

In Nairobi, Andrew Dirango tells Bendiksen about his life:

After I finished my courses here in Nairobi, I worked for British Airways and was doing quite well. But I lost my job and still have to live in the ghetto and move on with my life. I struggle. I have one daughter and my wife—I have to work hard and live with difficulties, with neighbours who have different thoughts. I can remember, during my first year with British Airways, I worked night shifts and returned home after midnight. One night, I was dropped off by car and walked a few steps. Suddenly, someone kicked me. I was down on the ground; then I saw someone coming toward me, right at me, with a knife. I screamed, God! I was beaten. They took my phone and my ID. I screamed for almost five minutes, but everyone was quiet in their houses.

After that I started living in fear. You never know what is going to happen. That’s how it is in the ghetto. I cannot say whether this is a bad life or a good life.

Published by Aperture, The Places We Live is an exceptional book, although it’s hard to find. But you can view more photos on the book’s website, or the Magnum site for the 2010 exhibition in Amsterdam.